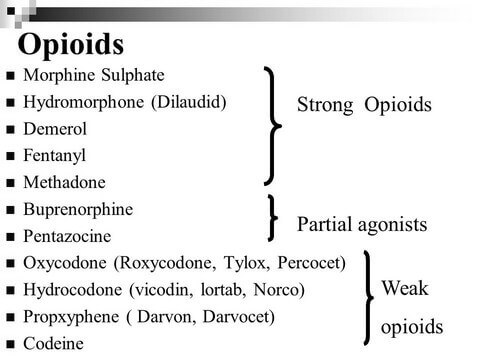

WEAK OPIOIDS

A collection of medications that include codeine, hydrocodone, and tramadol is recommended as the second tier of the WHO analgesic ladder. These are the weak opioids, and they are used for mild to moderate pain, often in combination with step 1 analgesics. Variation in the metabolism of weak opioids is considerable among individuals, which leads to a somewhat unpredictable analgesic effect. One way to minimize toxicity is to combine lower doses of agents from different classes of drugs to obtain additive or even synergistic effects while

staying within the tolerability limits of each agent. Hydrocodone and codeine are, for example, often compounded with APAP to take advantage of each agent’s different mechanism of action. Codeine itself has only a very weak direct analgesic effect, but it is metabolized in the liver to morphine. Codeine analgesic effects are thought to be due to the binding of morphine and subsequent active morphine metabolites to opioid receptors. Codeine also acts centrally to suppress cough. Some patients poorly metabolize codeine to morphine because of a genetic variation, and in these patients, codeine likely has little analgesic effect. Tramadol is thought to have effect on a wide variety of pain-modulating pathways. It is most notably a weak opioid receptor agonist and an SNRI. The tramadol active metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, is a stronger opioid receptor agonist than tramadol itself. Patients who are poor metabolizers of tramadol need relatively higher doses to achieve an analgesic effect because of decreased formation of the active metabolite. Tramadol should be used cautiously or not at all in patients taking other serotonin reuptake inhibitors because of a concern for serotonin syndrome.

Hydrocodone is a semisynthetic analogue of codeine that acts at various opioid receptors. In the United States, all commercially available hydrocodone formulations also include either APAP or ibuprofen. Hydrocodone has limited utility in very severe pain, because the dosing of hydrocodone is limited by the APAP or ibuprofen with which it is compounded.

STRONG OPIOIDS

Strong opioids make up step 3 of the WHO analgesic ladder. They are indicated for moderate to severe cancer pain or pain not adequately controlled by medications in the first two steps. Oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, buprenorphine, and methadone are examples of strong opioids. Patients with severe cancer pain should be initially treated with these medications rather than starting with weak opioids. The variability in opioid dose requirement is marked between different individuals and within individuals over time, which necessitates careful and ongoing dose adjustment.

Constipation, nausea, and vomiting are well-known adverse effects of opioid medications. Preventive therapy, such as with antiemetics and laxatives, should be available to patients taking opioid analgesics. If any particular opioid is not well tolerated by a given patient, administration of an equal analgesic dose of a different opioid may provide better pain control with fewer adverse effects. Physical dependence and tolerance are expected consequences of prolonged opioid use. Dependence is a physical state in which the body goes through withdrawal symptoms if a drug is stopped abruptly. If a medication is to be discontinued in a patient with physical dependence, it is important to slowly titrate off of the medication to avoid withdrawal. Tolerance refers to the loss of efficacy over time of a dose of medication that was previously effective. Dependence and tolerance should not be confused with addiction, which is a compulsive use of drugs for nonmedical reasons.

Another challenge, particularly for patients with progressive head and neck cancer, relates to oral intake restrictions, such that medication elixir formulations and nasogastric/ gastric tube utilization are often needed. IV, subcutaneous, transdermal, buccal, sublingual, rectal, epidural, intrathecal, and intraventricular routes are alternatives for analgesic administration.

Considerable controversy exists as to whether long-term opioid therapy is appropriate for patients with chronic noncancer pain. In addition to concerns of addiction or diversion, there are significant side effects with long-term opioid use that include hormone deficiency (leading to hypogonadism, osteoporosis, and other problems), decreased immune function, tolerance, dependence, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Furthermore, one study that looked specifically at facial pain found that 75% of patients failed to respond to opioid therapy, and many who took chronic opioids had functional decline. Because of the adverse effects of opioid therapy over months to years, other treatment modalities may be preferable, such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, NSAIDs, or interventional therapies.

Several guidelines have been proposed for the use of opioids in chronic noncancer pain.

Source: Cummings Otolaryngology, 6E (2015)